Well, I guess there’s much not to be liked in THE BIG BIRD CAGE, Jack Hill’s semi-sequel to his own superior THE BIG DOLL HOUSE (1971). Maybe that is even understandable, inasmuch as it was a project born out of the unexpected success of the first movie and the serious money it had made despite the very limited budget. Moreover, it was Hill’s intention to make a “proper” sequel to the first movie, but he didn’t have any of the original actors (but Pam Grier and Sid Haig) at hand as they were filming all over the Philippines in other productions. And, adding insult to adversity, Corman asked Hill to tone down the grittiness and violence of the first film in hopes of reaching an even wider audience. Yes, that’s the recipe to get something that will displease almost everyone who loved the first film.

But, weird guy that I am, I simply love THE BIG BIRD CAGE, despite all its faults. Yes, it is true that the violence is immensely toned down; and that the creepy warden and torturing guards are replaced here by a an histrionic warden obsessed with his “big bird cage” – a giant sugar mill of his own design – and a cadre of big fat unctuous homosexual guards that were as un-PC in 1972 as they are today (and more enjoyable for that). And even sexual violence is toned down and muted, peeking from behind the teasing promises of the abundant female flesh in exhibition here (I don’t remember seeing another movie with this ratio of nipple-slips).

But… the film has a lot of other points to commend it and, if you’re of the right frame of mind, to make you love it. For starters, the photography by Felipe Sacdalan (credited as Philip Sacdalan) is simply stunning in its use of colour and light when capturing some breathtaking Filipino locations around Luzon. Then we have the mad intricacy of the “big bird cage” itself, designed by Jack Hill’s own father, a veteran art director and set designer, and the man responsible for the creation of Disney’s Castle. And what to say of Hill’s own script, a delight of funny quips, smart comebacks and satiric comments that gains impetus all along the movie, never relenting, until the surprising body-count of the film’s finale?

All this adds up to create a fantasy world, a time that never-was, a hinterland of erotic dreams inhabited by beautiful, smart women, crazy homosexual men and fun amiable revolutionaries. And it is to the credit of Jack Hill that he could steer this mishmash of improbable elements, keeping it from veering too far into silliness or from falling down the pits of unfunny camp comedy. And trust me, there are plenty of laughs here; and it’s a joy to watch some very good actors having so much fun playing their parts.

Andy Centenera as the scenery chewing Warden Zappa and Sid Haig as the carefree and womanizer revolutionary leader play with gusto their opposite roles; Subas Herrero and Vic Diaz (both also appearing in BLACK MAMA, WHITE MAMA) are a delight to behold as the two chief gay guards that compete with one another for the attention of Haig when he infiltrates the prison working as a guard (the sole requisite seems to be being a homosexual).

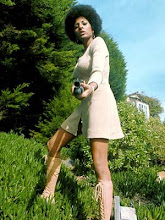

And then, we have the girls: first and foremost, the indomitable and unequalled Pam Grier, appearing here at her best: gorgeous, funny, tough, ad libing with gusto and getting to sing another catchy tune (if she wasn’t such a fine actress she could perfectly have had made it in the music world). This time she his surrounded by a host of gorgeous women (many of them in their first appearances, some of them in their only appearance in film): Anitra Ford as the seductress that gets arrested because she became a political liability because she’s been fucking the Prime-Minister; Candice Roman, the sprightly and cute blonde that has all the best lines; Teda Bracci (a real rock singer), the tough girl that commands respect and love both from her mates and the viewer; Carol Speed, the delightful black girl that suffers the cruellest death in the film and Rizza Fabian, the Mindanao exotic beauty that rats on the others because the Warden has a say over her son’s destiny.

It is impossible to cover in such a brief review all that goes on in this precious little exploiter. Sid Haig’s Django debating the politics of revolution with his followers that want to raid the female prison because they think the revolution needs more babies (“And do you have any particular bastille in mind?”, he asks). The government party that is inspecting the prison only to get fed up with the trite politically correct speech of the Warden: “Yes, yes, but lets us get to the girls”. And the two best lines of all: Carla (Roman) and Mickie (Speed) debating if Terry (Ford) is a “whore” or a “political”. “Among us, honest thieves and murderers, there’s nothing lower than a political”, says Carla. And when Mickie learns that Terry has been shagging the Prime-Minister: “See, I told her she was all right. She’s a whore”, before Carla observes that she isn’t making it for the money. “She’s not a whore! She’s political!”

But the belly-breaker roll-on-the-floor moment belongs to Vic Diaz. When Terry tries to escape from prison, she ends up about to be gang-raped by some guys to whom she asks to use a phone (yeah, really). She is spared from a fate worse than death (“You can’t rape me…”, she said early on to Django. “I like sex!”) by the sudden arrival of Diaz’s Rocco with some soldiers and the search dogs. Quickly grasping what was going on, and looking from the horny Filipinos to the semi-naked Terry, he just mutters: Oh darn. Nothing like that ever happens to me.

On the whole, THE BIG DOLL HOUSE is great fun. It rehashes some of the ingredients of the previous film and either improves or comments on them through a kinf of don’t-take-it-so-seriously wink of the cinematic eye. Pam Grier is, if possible, even more lovely In this film. She improvised the line “It’s miss nigger to you” when she docks another inmate that calls her nigger. We are also treated to some scenes in the exterior, as well as to a collective mud fight, before arriving at the explosive final battle, with its desperate dash through the jungle, heroic deaths and accounts settled. It is eye-candy of a superior quality and harks back to a time when doing indie cinema meant doing fun, over the top movies, instead of the mushy moralizing pseudo-cine verité crap that comes out of Sundance every year.

And you could still be political while doing it. Not just a commercial whore.